The Taliban also secured the people from widespread infighting among various Mujahideen factions, which they referred to as forces of shar-aw-fasad (wickedness and corruption). In recent years, however, life has become nastier and more brutish for the people of Afghanistan-again because of an even older insight of the Roman historian Tacitus: ‘Formerly we suffered from crimes, now we suffer from laws.’ We will argue that the insight by Tacitus also applied when the Taliban became the Leviathan in 1996, providing Afghans with greatly enhanced security against marauding criminal gangs and armed militia groups. After 2001, a Leviathan, President Hamid Karzai, backed by the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), increased security at first in the way predicted by Hobbes. Afghanistan has since 1978 suffered much worse violence from various warring factions (including those who formed states) than England endured during Hobbes’s lifetime. The Leviathan could be a monarch or some other authority that takes central control of a state.

His conclusion was that life is nasty, brutish and short until a Leviathan ( Hobbes 1651) emerges who can be granted legitimacy to pacify a space by dominating all other armed factions inside it. Thomas Hobbes lived through the terror and security dilemmas of the English Civil War. A more Jeffersonian rural republicanism that learnt from local traditions of dispute resolution defines a path not taken. One answer to that question was jirga/shura. The West failed to ask in 2001 ‘What is working around here to provide people security?’. While the US diagnosis of anomie in Afghanistan up to 2009 was aptly Hobbesian, its remedy of supporting President Hamid Karzai as a Leviathan was hardly apt. Police were widely perceived as thieves of ordinary people’s property, not protectors of it. Polls suggest judges were perceived as among the most corrupt elements of a corrupt state.

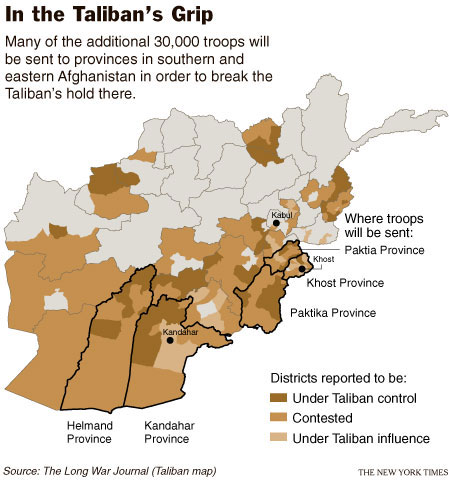

The Taliban returned with a parallel court system that most Afghans viewed as more effective and fair than the state system. After the Taliban’s ‘defeat’ in 2001, their resurgence was invited by the failure of state justice and security institutions. The Taliban came to power because they were able to restore order to spaces terrorized by armed gangs and Mujahideen factions. Editorially, FDD tends to remain neutral when discussing political issues, however, at times they are critical of President Trump’s foreign policy, such as this: Trump caves to Pakistan on Afghanistan.This article views Afghanistan less as a war, and more as a contest of criminalized justice systems. In another sample story, Several districts change hands as fighting rages in northern Afghanistan, there is again proper sourcing to local media as well as DW.com and the Afghanistan Times. This story is appropriately sourced to Politico and the Afghanistan Ministry of Defense. Headlines contain minimal loaded language such as this: Taliban supplies al Qaeda with explosives for attacks in major Afghan cities. Story selection often fits within their stated mission of covering the war on terror. In review, FDD’s Long War Journal covers stories about countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Iraq and follows the actions of al Qaeda and its affiliates. Many of their large donors hold pro-right wing Israeli ideology. The Foundation for Defense of Democracies is funded through small and large donors such as Abramson Family Foundation and Sheldon Adelson. The website is published by Public Multimedia, Inc and accepts donations. The FDD has been described as Neo-conservative and Pro-Israel. FDD is headed by President Cliff May, and CEO Mark Dubowitz. FDD’s Long War Journal is a project of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)